China’s footprint in Bangladesh has expanded rapidly over the past decade—bridges, power plants, ports, and roads built with steel, machines, and manpower flown in from Beijing. Unlike the financial support from institutions like the World Bank, ADB, or JICA—typically disbursed in tranches, monitored closely, and executed via local contractors—Chinese investments often arrive as complete packages: funding, labor, materials, and execution, bundled into one.

This model, known as the “resources-for-infrastructure” or EPC+F (Engineering, Procurement, Construction + Financing), is not unique to Bangladesh. It is China’s signature approach across Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. But does this model truly fit Bangladesh’s development context?

A Short History of Chinese Investment in Bangladesh

Chinese economic engagement with Bangladesh gained momentum after 2010, with major traction post-2016 when Xi Jinping’s landmark Dhaka visit produced agreements worth over $24 billion in loans and investments.

Key investments and commitments include:

- Padma Bridge Rail Link Project – $3.14 billion, executed by China Railway Group Ltd

- Payra Thermal Power Plant – $2.5 billion, a joint venture with China National Machinery Import and Export Corp

- Karnaphuli River Tunnel (Bangabandhu Tunnel) – $705 million, executed by China Communication Construction Company

- Dasherkandi Sewage Treatment Plant – first of its kind in Bangladesh, fully constructed by Chinese firms

By 2022, China had become the largest trading partner of Bangladesh and one of its top FDI sources, with investments particularly concentrated in infrastructure and energy.

The Positives: Why Chinese Investment Works

Speed and Scale: Chinese companies are capable of mobilizing equipment, labor, and capital rapidly—leading to quicker implementation of mega projects. Turnkey Execution: The Chinese EPC+F model reduces bureaucratic delays common in multilateral-funded projects. There’s less red tape, and project deadlines are more aggressively pursued. Financing Flexibility: Many Chinese loans come with fewer political or governance conditions compared to World Bank or ADB disbursements. Strategic Gaps Filled: Power generation, bridges, and digital connectivity—where Bangladesh lacked technical expertise—have significantly benefited from Chinese know-how.

The Concerns: Why the Model May Not Fit Bangladesh Perfectly

Low Local Employment: Most Chinese projects import labor, equipment, and management, leaving limited room for local engineers, contractors, or workers. Technology Transfer Deficit: Unlike JICA or EU-funded projects, Chinese investments rarely include structured skills training or knowledge transfer programs for locals. Debt Sustainability Questions: Although Bangladesh’s external debt-to-GDP ratio remains manageable (~20%), the terms of some Chinese loans are opaque, and there are fears of over-dependence. Bypassing Local Ecosystems: Chinese firms often operate in silos—contracting within their own ecosystem. This undermines local construction firms, suppliers, and long-term capacity-building. Geopolitical Sensitivities: Bangladesh’s strategic balancing act between India, China, and the West becomes delicate as Chinese economic presence grows.

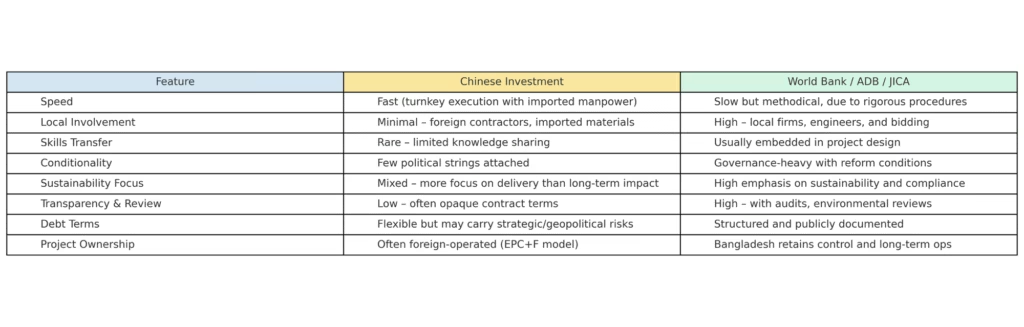

A Tale of Two Models: Multilateral vs. Chinese Funding

Recent Developments and Trends (2023–2025)

Slower Project Uptake: Bangladesh has begun reassessing some China-funded projects, particularly after the pandemic, due to rising cost concerns and lack of local benefit. China-Bangladesh Digital Collaboration: Huawei has continued expanding its footprint in telecom and smart city projects, raising both hope and cybersecurity concerns. Special Economic Zones (SEZs): China is developing a dedicated Chinese Economic Zone in Chittagong—if structured well, this could become a model for export-led local employment.

The Middle Path: Learning to Fit the Glove

Rather than rejecting the Chinese model, Bangladesh must restructure the terms:

Mandate 30%+ local workforce quotas in large EPC contracts Negotiate joint ventures with Bangladeshi firms, not standalone Chinese control Demand technology transfer components as part of the investment deal Ensure transparent procurement and parliamentary review of large bilateral loans

Conclusion: A Most Welcome Handshake—But Time to Tailor the Fit

China’s investments are not inherently problematic—they have filled critical gaps where Bangladesh had neither time nor technical expertise. But development is not just about structures—it’s about systems, skills, and sovereignty. The glove that fits Africa or Laos may need tailoring in Dhaka.

So yes, the Chinese model is welcome—but only if it evolves from being project-based to partnership-based. Bangladesh must now negotiate smarter, not just faster.