As Bangladesh enters the final leg of its “Smart Bangladesh” roadmap, the national budget for fiscal year 2025–26 reveals both ambition and ambiguity in its treatment of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector. While some allocations signal continuity with digital transformation goals, others suggest fiscal hesitation at a moment when the country needs bold tech investment to compete globally.

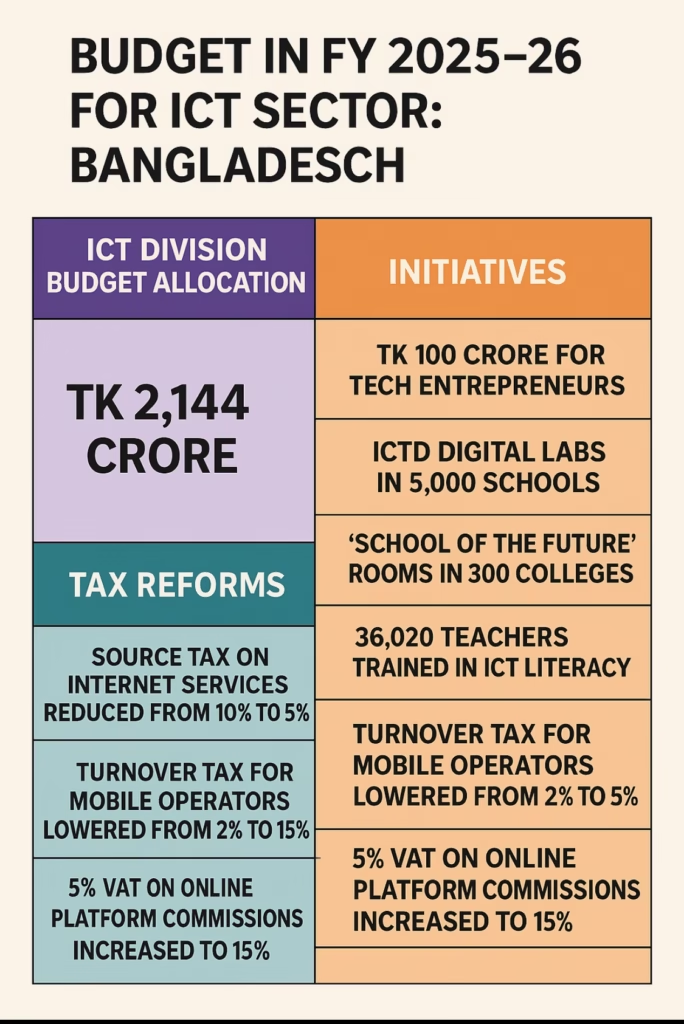

The government has proposed a Tk 2,144 crore allocation for the ICT Division, a substantial reduction from Tk 2,872 crore in the previous fiscal year. The number may look like mere belt-tightening amid broader economic constraints, but for a sector pegged as the engine of Smart Bangladesh, this is more than just symbolic. It’s a signal.

What makes this contradiction starker is the government’s continued rhetoric about making Bangladesh a regional ICT hub. Simultaneously, Tk 100 crore has been allotted for tech entrepreneurs—a laudable move on paper, but one that lacks the ecosystem maturity or follow-up detail to be transformative. Bangladesh’s startups don’t just need seed money—they need global payment gateways, IP protection, skilled mentorship, and access to scalable infrastructure. The budget speaks little of those systemic gaps.

There are some bright spots. The expansion of ICTD Digital Labs to 5,000 schools and the creation of “School of the Future” rooms in 300 colleges point to a recognition that future readiness begins in the classroom. These efforts, if implemented well, could help democratize access to emerging technologies like robotics and coding. The plan to train 36,020 teachers and establish IT training centers in 491 upazilas also shows a bottom-up approach to digital inclusion.

On the taxation front, the reduction of source tax on internet services from 10% to 5% is a direct win for internet penetration—an essential condition for remote education, freelancing, and digital commerce. Similarly, the turnover tax for mobile operators was reduced from 2% to 1.5%, slightly easing operational pressure in a capital-intensive sector.

Yet, there’s an undercurrent of contradictions. The government extended VAT exemptions for local mobile handset production until 2027, but simultaneously increased VAT rates on finished handsets to 7.5–10%, and hiked VAT on online platform commissions from 5% to 15%. Add to that a 10% supplementary duty on OTT platforms, and you see a curious pattern: encourage digital infrastructure, but penalize its use.

Such disjointed policies risk dulling the momentum of digital transformation. Entrepreneurs may find it harder to scale; content creators may migrate to informal platforms; and consumers may absorb rising costs just to stay connected.

Where the budget truly missed an opportunity is in strategic foresight. No significant funding has been earmarked for AI research, blockchain-based public service delivery, or national cybersecurity infrastructure—three pillars essential for any digital nation in the 2025 landscape. Even the One-Stop Service (OSS) for business licenses, long touted as an e-governance milestone, receives scant operational detail in this year’s financial plan.

As a nation, Bangladesh is standing at the edge of a digital leap—but this budget doesn’t yet reflect a confident leap forward. It’s more a cautious shuffle.

The future of Bangladesh’s ICT growth will depend not just on allocations but on execution, monitoring, and cross-sectoral policy harmony. A well-funded project with poor coordination can do more harm than a smaller initiative with laser focus and clear accountability.

In a world where digital disruption defines national competitiveness, Bangladesh’s budget choices need to be sharper, bolder, and more coordinated. This year, the ambition is present—but the urgency is not.

About the Author:

Md Shofiul Alam is a cognitive AI researcher, tech policy strategist, and founding author of Bangladesh’s National AI Strategy. He writes on the intersection of technology, governance, and global south innovation.